That's the way I felt when I began reading Matt Kindt's Mind Mgmt. (the not sure what's going on aspect, not the porn question) - a bit nonplussed, but in a great way. I've been an admirer of well-crafted solipsistic paranoia since The Prisoner first ran on American TV.

A plane lands with everyone aboard, save one girl, afflicted with amnesia.

The girl in question becomes a reluctant celebrity as a result of the incident. She authored a bestseller based on her experiences, but her career since then has been precarious at best.

Her daily life as an investigative journalist is hampered by her insistence on delving into The Event, as it comes to be known, at the expense of her current assignments.

As you might surmise, there's more going on here than even those cryptic events imply.

Our heroine, Meru, is propelled into an international journey of discovery, searching for the mysterious figure known only as The Manager.

The obvious comparisons apply. The work evokes Kafka, Phillip K. Dick, the aforementioned The Prisoner, and in some senses, more mainstream paranoia like The X-Files and its predecessor Kolchak, the Night Stalker, though the paranormal plays a diminished role in Mind Mgmt.

|

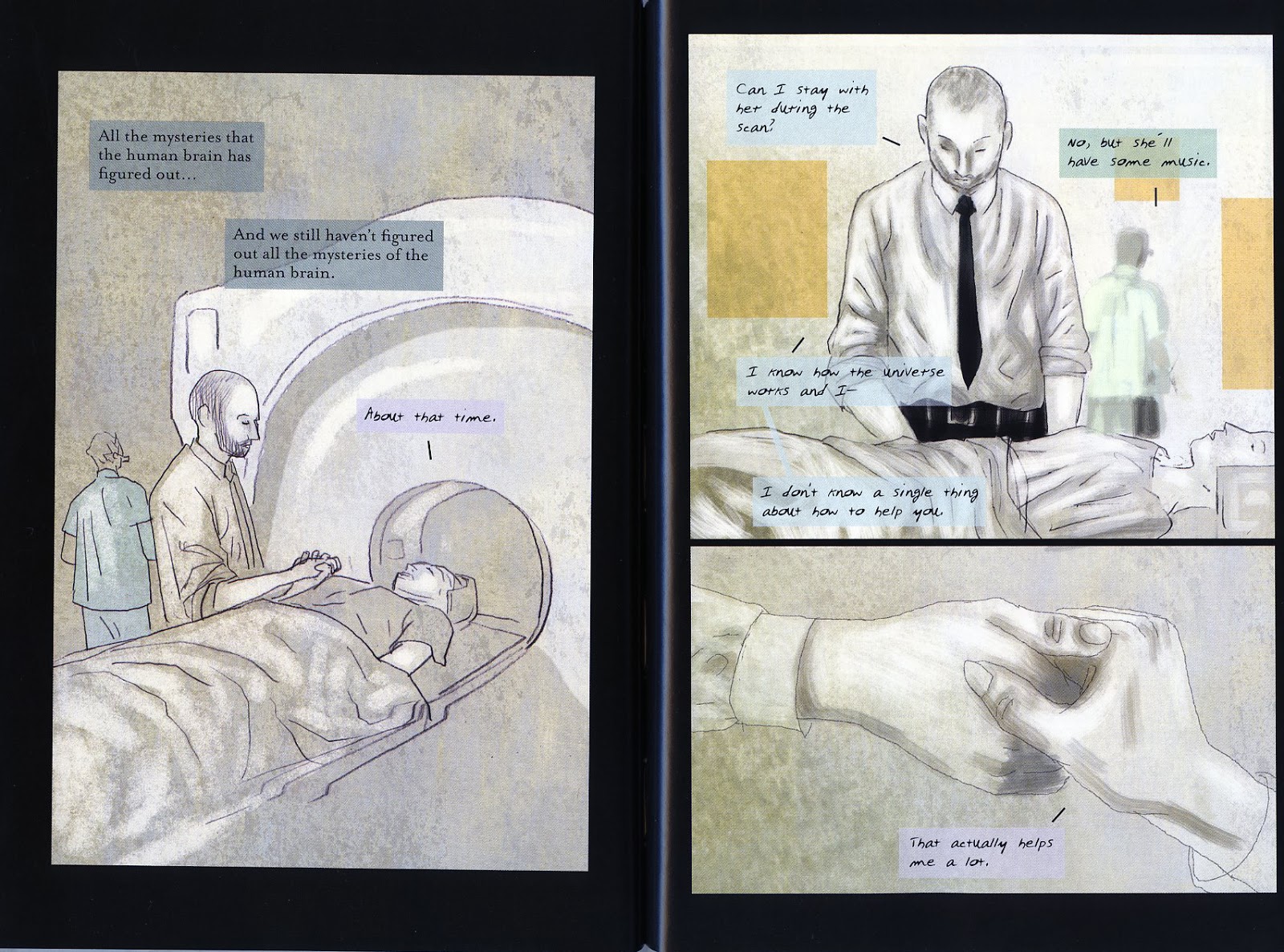

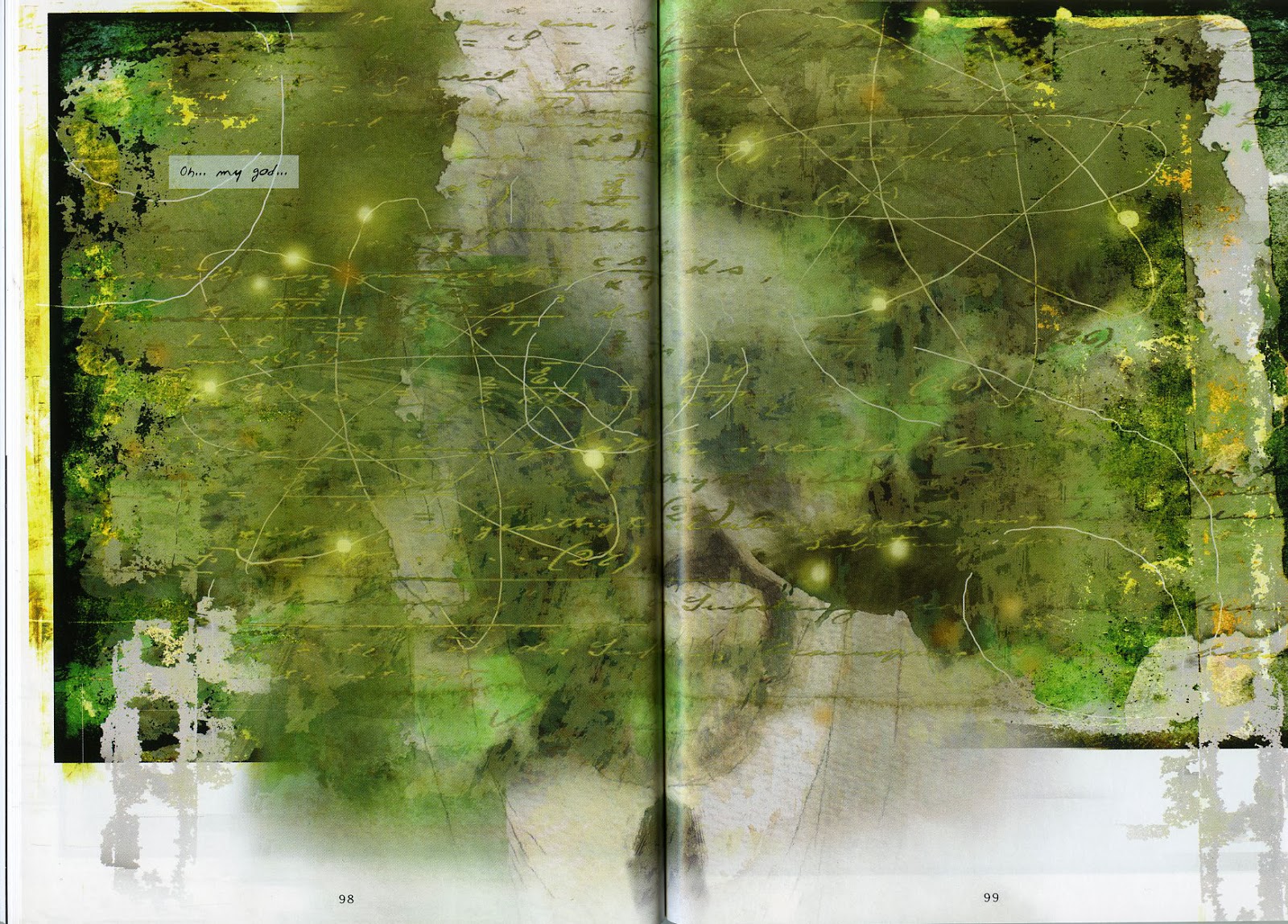

| Note the border elements/story! |

I've had sporadic and passing acquaintance with Kindt's other work. I enjoyed his work on the New 52 Justice League series, but an earlier solo work, 2 Sisters, left me cold. Very well crafted, but just too melancholy and too detached for my tastes. In contrast, though it also has its morose aspects, his work on Frankenstein, Agent of S.H.A.D.E. is an over-the-top romp through the best chaos that escapist fiction has to offer. He also contributed some material to Jeff Lemire's wonderful Sweet Tooth. Kindt's 3 Story: The Secret History of the Giant Man is on my short list for catching up on my reading, and has been optioned for filming.

Meanwhile, back at the story:

|

| Kindt's design and color sense are also vital parts of the story. |

Next: Best Comics of 2013, No. 3: a tie!