I've read more histories of comics than some folks have had hot breakfasts. The books all have their errors and omissions, some better than others. But there's been a gradual sophistication of the study, to the point we are now at, where a sufficient body of research has accumulated that it's beginning to take cohesive form. This results in a sort of canon of accepted notions, things taken as verbatim and rarely questioned outside academia.

Enter The Comic Book History of Comics.

A history done in comic book format. Nice. This has been appearing sporadically in single issue format over the last few years. I used the first two issues, covering Bronze and early Golden Ages, as a text in my Comic Book History class shortly after they came out. I was frustrated by the books' arriving three months after they were ordered(!), making them fundamentally useless for aiding in that portion of the course.

Now, however, there's a spiffy, gosh-wow no-sarcasm-intended really cool collected edition of this, from our friends at IDW Publishing, who have been doing some wonderful work, both with new comics and with reprints - would that I had the funds for any of their Artist's Edition series - and publishing this as a collection continues that trend.

I will be using this for a textbook in Comic History class, now that it's available in a decent uniform edition, if I get the opportunity.

However, it's not without its flaws. I list these while recognizing that the creators of the book have requested notification of errors and omissions, for correction in future volumes. However, I wrote them about a couple of the things I'm discussing here prior to the work being collected, and the errors I wrote about are still there.

The first line of the first (disclaimer) text page reads, "this comic book is a work of historical scholarship."

Really?

Then where's the index?

Scholarship on history implies use as reference. You'd think an index would be a no-brainer. In fairness, the book does include a decent section of Notes on Sources, with more on the book's web page, which is always a useful tool in research and citation.

There are some other problems here. Right off the bat, Fred van Lente (writer) and Ryan Dunlavey (artist) jump in with the Yellow Kid's 1896 debut in Hogan's Alley, citing it as the first comic strip. This completely ignores Ally Sloper's Half Holiday, a British strip that began in 1874.

I'm not going to pick the book apart page by page. Most of it is quite good, if a little heavy on the sarcasm and snark for my taste.

But there are some omissions and factual errors that are too glaring to ignore.

The coup d'etat involving Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson being underhandedly bought out by Harry Dondenfeld and Jack Liebowicz, covered in depth in Geeks, Guns and Gangsters and in Larry Tye's recent volume Superman, is reduced to one line on page 32. Since these events lead directly to the formation of DC Comics as we now know it (and are exacerbated by a Wheeler-Nicholson story appearing in Action Comics no.1, the book being discussed herein), it does deserve more than one line, especially a line that dismisses all the nuance of the facts.

Similarly, although The Shield is shown on page 58, there's no mention of his creation predating that of Captain America. Indeed, The Shield isn't even mentioned by name. This pattern recurs in other parts of the book. Cheech Wizard appears on page 206, inexplicably in a section on the early 1990s speculation market (which, given that Cheech is something of huckster, is somewhat apropos), but neither Cheech nor his creator Vaughn Bode' are mentioned in the section on undergrounds.

In fact, the entire New York underground scene is only mentioned,and the Comix from Wisconsin's Kitchen Sink Press and the Chicago underground scene are ignored.

The discussion of Wertham and the Comics Code is accurate as far as it goes, but it leaves out the Code's two major precursors: The Association of Comic Magazine Publishers Code of 1948 (which also had a seal used on covers!), and the in-house editorial code of Fawcett Comics, shown in Chip Kidd's book SHAZAM!

The section on graphic novels mentions the early work of Lynd Ward and Franz Maesreel but neglects Milt Gross's 1930 classic He Done Her Wrong, in print from Fantagraphics. But Sabre, a graphic novel from Eclipse, Sabre, whose publication predates that of A Contract With God (albeit only by a few months) is ignored.

They do manage to cite Gil Kane's Blackmark and His Name is Savage in this context, and rightly so, along with the 1950 It Rhymes With Lust. However, the followup paperback The Case of the Winking Buddha, is overlooked. In fairness, the latter work is of lesser quality, but we're talking history here, not aesthetics.

Some of these things might seem a tad nit-picky. Maybe so. They're significant to me, but not necessarily to the average reader. Still if this is the average reader's first exposure to comics history, that reader might take these things as Gospel unquestioningly.

But the most glaring error is almost an insult.

There are no female creators mentioned in the entire book. Not one.

I usually don't do the big text thing, but it seems correct to do so here.

No mention of Lily Renee', Marie Severin, Ramona Fradon, Lee Mars, Colleen Doran, Jan Duuresema, Trina Robbins, Shelby Sampson, Alison Bechdel, Mary Wings, Roberta Gregory, Selby Kelly, or the great neglected Shary Fleniken, whose work was in at least one of the Air Pirates books, though she wasn't named in the suit.

And that list was just off the top of my head. There are so many more that could be recognized, especially in the last 30 years.

The only mention of women cartoonists in the entire book is in the section on romance comics, page 60: "Though through our allegedly more enlightened "modern" eyes, romance comics may be seen as simply re-inscribing the more patriarchal aspects of American society (as 99.99% of them were written and drawn by men)..."

That's it. A backhanded acknowledgment of the supposed .01% of comic artists and writers of the 1940s who were female. That's the whole of the discussion of female creators of comics in this history.

Again, that doesn't invalidate the book. Neither does it make the book inherently bad. It's mostly really good. What is here is reasonably well-researched and presented in an entertaining (if often drenched in fanboy attitude ) fashion.

I will use this as a text, but I will expect my students to pore over it with a microscope.

No history of anything can be perfect, but this one has a few really big holes.

Insights about comics, prog rock, classic cartoons and films, higher education, sexuality and gender, writing, teaching, whatever else comes to mind, and comics. I know I said comics twice. I like comics!

Showing posts with label Graphic novel. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Graphic novel. Show all posts

Wednesday, June 13, 2012

Monday, February 7, 2011

"The Congressman from Georgia has the word ballon..."

It's been announced at The Beat and at Bleeding Cool (see links on left) that GA Representative John Lewis will be writing a graphic novel for Top Shelf.

Top Shelf has done some innovative work, including a handsome edition of Moore and Campbell's FROM HELL, Jeff Lemire's pre-Sweet Tooth work Essex County, the continually fascinating and frustrating League of Extraordinary Gentlemen series from Masters Moore and O'Neill, and the popular (with everybody but me) Blankets by Craig Thompson.

A couple things need to be noted.

First, no artist has been named at this point.

Second, this book is based on Lewis' experiences during the 1960s Civil Rights Movement.

To quote an article in the Tuscon Citizen, reprinted in USA Today:

"As a young man, Lewis was beaten in Selma, Ala., on the day in 1965 that has become known as Bloody Sunday. Marchers were on their way from Selma to Montgomery when Lewis and others were beaten by Alabama state troopers on the Edmund Pettus bridge."

That's Lewis on the left, next to Dr. King.

Sounds like a promising project, and I'm eager to read it, but all accounts imply that Lewis and his co-writer, Congressional staffer Andrew Aydin, are doing a factual account of events. Shouldn't this then be categorized as "graphic memoir" a la Fun Home or released without categorization, like Harvey Pekar's underrated and revolutionary Macedonia?

Perhaps it should just be called a "graphic history" like Harvey's history of The Beats.

Does it matter?

For the umpteenth time, yes. If the diverse potential of the form is to be recognized, it cannot be seen as just one thing. That would be akin to referring to all long-form narratives as novels, rather than recognizing their variations as epic poetry, screenplays, or religious texts like the Gita or the Bible.

Beyond that, there's the issue of veracity. Howard Cruse was taken to task, rather unfairly, I thought, by comic creator Ho Che Anderson for Cruse's memories of the times around the Civil Rights Movement in Stuck Rubber Baby. So questions of fiction/nonfiction/metafiction are concerns here as well.

Finally, the news accounts are sort of true.

This is the first time a Congressman has authored a graphic novel. But he's not the first Congressman who worked in the comics form!

That distinction goes to John Miller Baer, whose comics first ran in the Non-partisan Leader in 1916.

He served one term as a US Representative from North Dakota. He was not re-elected, and returned to his first loves, journalism and political cartooning. His cartoons were primarily concerned with farmers' rights and the evolution of granges.

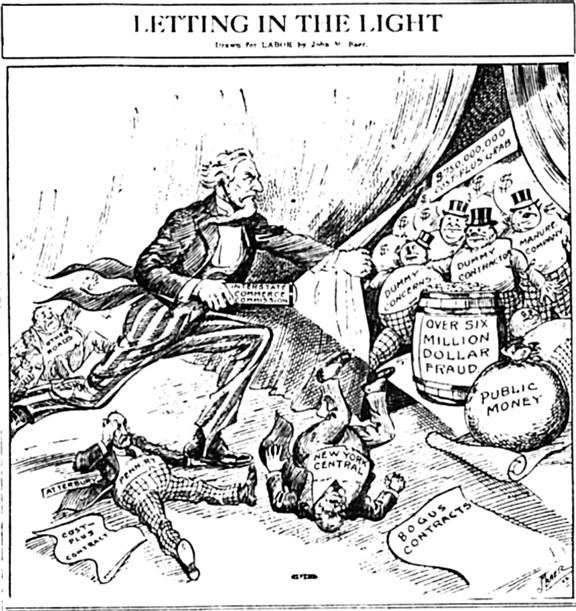

His work was stylistically typical of the period, heavy on detail and tentative in its handling of text.

Thematically, his message was a departure from the more well-known political cartoonists that preceded him. Winsor McCay, for example, though a humanist, was very much in keeping with some of the more stringent political views of his employer, William Randolph Hearst. McCay's views on social problems manifest in many of his own works, notably the film Sinking of the Lusitania.

So carry on, Representative Lewis! You are following a proud tradition, whether you know it or not!

I love telling my Comics History students about Baer. Thanks to the innovative efforts of Rep. Lewis, who is scheduled to receive the Congressional Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor, later this month, I have a window to share Baer's achievement here as well.

Left: one of Baer's cartoons, for your, ahem, scholarly review.

Below:

Cartoonist (and Congressman) Baer.

Top Shelf has done some innovative work, including a handsome edition of Moore and Campbell's FROM HELL, Jeff Lemire's pre-Sweet Tooth work Essex County, the continually fascinating and frustrating League of Extraordinary Gentlemen series from Masters Moore and O'Neill, and the popular (with everybody but me) Blankets by Craig Thompson.

|

| Representative Lewis and co. |

A couple things need to be noted.

First, no artist has been named at this point.

Second, this book is based on Lewis' experiences during the 1960s Civil Rights Movement.

To quote an article in the Tuscon Citizen, reprinted in USA Today:

"As a young man, Lewis was beaten in Selma, Ala., on the day in 1965 that has become known as Bloody Sunday. Marchers were on their way from Selma to Montgomery when Lewis and others were beaten by Alabama state troopers on the Edmund Pettus bridge."

That's Lewis on the left, next to Dr. King.

Sounds like a promising project, and I'm eager to read it, but all accounts imply that Lewis and his co-writer, Congressional staffer Andrew Aydin, are doing a factual account of events. Shouldn't this then be categorized as "graphic memoir" a la Fun Home or released without categorization, like Harvey Pekar's underrated and revolutionary Macedonia?

Perhaps it should just be called a "graphic history" like Harvey's history of The Beats.

Does it matter?

For the umpteenth time, yes. If the diverse potential of the form is to be recognized, it cannot be seen as just one thing. That would be akin to referring to all long-form narratives as novels, rather than recognizing their variations as epic poetry, screenplays, or religious texts like the Gita or the Bible.

Beyond that, there's the issue of veracity. Howard Cruse was taken to task, rather unfairly, I thought, by comic creator Ho Che Anderson for Cruse's memories of the times around the Civil Rights Movement in Stuck Rubber Baby. So questions of fiction/nonfiction/metafiction are concerns here as well.

Finally, the news accounts are sort of true.

This is the first time a Congressman has authored a graphic novel. But he's not the first Congressman who worked in the comics form!

That distinction goes to John Miller Baer, whose comics first ran in the Non-partisan Leader in 1916.

|

| A rare color piece by Baer |

He served one term as a US Representative from North Dakota. He was not re-elected, and returned to his first loves, journalism and political cartooning. His cartoons were primarily concerned with farmers' rights and the evolution of granges.

His work was stylistically typical of the period, heavy on detail and tentative in its handling of text.

Thematically, his message was a departure from the more well-known political cartoonists that preceded him. Winsor McCay, for example, though a humanist, was very much in keeping with some of the more stringent political views of his employer, William Randolph Hearst. McCay's views on social problems manifest in many of his own works, notably the film Sinking of the Lusitania.

So carry on, Representative Lewis! You are following a proud tradition, whether you know it or not!

I love telling my Comics History students about Baer. Thanks to the innovative efforts of Rep. Lewis, who is scheduled to receive the Congressional Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor, later this month, I have a window to share Baer's achievement here as well.

Left: one of Baer's cartoons, for your, ahem, scholarly review.

Below:

Cartoonist (and Congressman) Baer.

Friday, October 22, 2010

Comics? Museums? How perfectly too-too.

The announcement of a museum exhibit on graphic novels at the James A. Michener Museum of Bucks County is challenging in several ways.

While museum exhibits of comic art in the US and Canada date back to the 1970s (earlier exhibitions happened in Europe, but the only one I can find a a record of is the 1968 exhibition of comic-strip art at Musée des arts decoratifs, Palais du Louvre) with the Steranko: Graphic Narrative show in Winnipeg, the 1980s and the Whitney Comic Art show, involvement of Art Speigleman in the Beyond High & Low show in response to the High & Low Show at MOMA, their presence, while desirable, poses other challenges.

Comics are relatively accepted as an art form now, due in no small part to the Graphic Novel demarcation. Note that the exhibit at the Michener is a "graphic novel" exhibit, not a "comic art" exhibit, despite using panels from a Spirit comic, not a graphic novel per se, in its informational web page. Also, please take note of the sloppy research in attributing the nomenclaute of "commonly accepted as the first graphic novel" to A Contract With God. While the significance of this book cannot and should not be denied, even Eisner acknowledged Masreel's woodcut books as predecessors. Others worked in "wordless books", and the term "picture novel" was used on the cover of the 1950 paperback It Rhymes With Lust and its successor from the same publisher, Case of the Winking Buddha.

The original It Rhymes With Lust has been reprinted twice, first in The Comics Journal and second as a facsimile edition with a new foreword from Dark Horse Comics, the third largest comic company in the US.

Are we to infer sloppy research on the part of the Michener Gallery in its statement that A Contract With God is " is commonly accepted as the first to be called a graphic novel", or is that simply a limitation of copy space, since Milt Gross's name is also cited as being part of the exhibit? Gross's He Done Her Wrong, a 1930 book billed as "The Great American Novel in Pictures", back in print from Fantagraphics, is another work that predates Eisner.

This is journeyman stuff. Any undergrad researcher could discover most of this in a matter of a few minutes.

However, it's rather easy to get one's back up about such things. It may very well be a case of sloppy copy writing and nothing more, especially given the inclusion of Gross in the exhibit. And as comics scholars, many of us have a slight persecution complex. No, really, we do!

All that given, there's the larger question of acceptance and its related costs and advantages.

True, comics are now in museums, although often trough the aforementioned back door of the "graphic novel". The notable exceptions are museums devoted to comics, like San Francisco's stunning Cartoon Art Museum, whose current show, Graphic Details: Confessional Comics by Jewish Women includes the work of old friend Trina Robbins. We've linked to Trina's site numerous times, so one more won't hurt!

What do we gain and what do we lose by comics gaining social acceptance?

For one thing, comics may wither. This is a possible byproduct of the acceptance of manga and graphic novels. After all, why pay $3 -4 per issue for "floppies", old school flimsy paper comics of 24 -32 pages including ads, when you could wait for the collection (not properly a "graphic novel", unless that was the creators' initial intent) and get the whole thing in a more durable form for a lower cumulative price, in many cases?

That's a bit a doom and gloom thing. I firmly believe that the floppy, or conventional comic book, will endure in some capacity, much as live theater still exists but is no longer the entertainment/cultural mainstay it was once was. However, when great books like daytripper sell a meager 9,800 copies, it's hard to avoid a small sense of foreboding.

The other thing we lose with social acceptance of comics is the imprimatur of the outlaw cachet.

So many things regarded as social taboos- pinball, motorcycles, tattoos, comics- have been accepted, with that acceptance ranging from a near-mandate (tattoos) to becoming passe' (pinball). The cadre of misfits has been assimilated to varying degrees.

That has its up side. Comics are a more than valid art form, and deserve to be taken seriously, contingent on content, of course. I have little patience for the latest bombastic, senses-shattering, "this will change everything" multi-book epic from Marvel or DC. Civil War was socially relevant and genuinely important as a metaphor for a divided nation at odds over the false distinction between freedom and security. Crisis on Infinite Earths was a necessary bit housecleaning, with some strong storytelling. They're worthwhile and fun. But enough grandeur already. Just tell me a decent story and I'm there.

My point is that comics deserve to be taken seriously, AS COMICS. Museums are great and comics deserve a place in them. But please don't damn them with faint praise by insisting on the "graphic novel" badge to "legitimize" the work. A great show of Comic Book Art needs no excuses for itself.

It's a bloody comic book. That's all it needs to be. If it's a good one, let it stand on its own merits.

While museum exhibits of comic art in the US and Canada date back to the 1970s (earlier exhibitions happened in Europe, but the only one I can find a a record of is the 1968 exhibition of comic-strip art at Musée des arts decoratifs, Palais du Louvre) with the Steranko: Graphic Narrative show in Winnipeg, the 1980s and the Whitney Comic Art show, involvement of Art Speigleman in the Beyond High & Low show in response to the High & Low Show at MOMA, their presence, while desirable, poses other challenges.

Comics are relatively accepted as an art form now, due in no small part to the Graphic Novel demarcation. Note that the exhibit at the Michener is a "graphic novel" exhibit, not a "comic art" exhibit, despite using panels from a Spirit comic, not a graphic novel per se, in its informational web page. Also, please take note of the sloppy research in attributing the nomenclaute of "commonly accepted as the first graphic novel" to A Contract With God. While the significance of this book cannot and should not be denied, even Eisner acknowledged Masreel's woodcut books as predecessors. Others worked in "wordless books", and the term "picture novel" was used on the cover of the 1950 paperback It Rhymes With Lust and its successor from the same publisher, Case of the Winking Buddha.

The original It Rhymes With Lust has been reprinted twice, first in The Comics Journal and second as a facsimile edition with a new foreword from Dark Horse Comics, the third largest comic company in the US.

Are we to infer sloppy research on the part of the Michener Gallery in its statement that A Contract With God is " is commonly accepted as the first to be called a graphic novel", or is that simply a limitation of copy space, since Milt Gross's name is also cited as being part of the exhibit? Gross's He Done Her Wrong, a 1930 book billed as "The Great American Novel in Pictures", back in print from Fantagraphics, is another work that predates Eisner.

This is journeyman stuff. Any undergrad researcher could discover most of this in a matter of a few minutes.

However, it's rather easy to get one's back up about such things. It may very well be a case of sloppy copy writing and nothing more, especially given the inclusion of Gross in the exhibit. And as comics scholars, many of us have a slight persecution complex. No, really, we do!

All that given, there's the larger question of acceptance and its related costs and advantages.

True, comics are now in museums, although often trough the aforementioned back door of the "graphic novel". The notable exceptions are museums devoted to comics, like San Francisco's stunning Cartoon Art Museum, whose current show, Graphic Details: Confessional Comics by Jewish Women includes the work of old friend Trina Robbins. We've linked to Trina's site numerous times, so one more won't hurt!

What do we gain and what do we lose by comics gaining social acceptance?

For one thing, comics may wither. This is a possible byproduct of the acceptance of manga and graphic novels. After all, why pay $3 -4 per issue for "floppies", old school flimsy paper comics of 24 -32 pages including ads, when you could wait for the collection (not properly a "graphic novel", unless that was the creators' initial intent) and get the whole thing in a more durable form for a lower cumulative price, in many cases?

That's a bit a doom and gloom thing. I firmly believe that the floppy, or conventional comic book, will endure in some capacity, much as live theater still exists but is no longer the entertainment/cultural mainstay it was once was. However, when great books like daytripper sell a meager 9,800 copies, it's hard to avoid a small sense of foreboding.

The other thing we lose with social acceptance of comics is the imprimatur of the outlaw cachet.

So many things regarded as social taboos- pinball, motorcycles, tattoos, comics- have been accepted, with that acceptance ranging from a near-mandate (tattoos) to becoming passe' (pinball). The cadre of misfits has been assimilated to varying degrees.

That has its up side. Comics are a more than valid art form, and deserve to be taken seriously, contingent on content, of course. I have little patience for the latest bombastic, senses-shattering, "this will change everything" multi-book epic from Marvel or DC. Civil War was socially relevant and genuinely important as a metaphor for a divided nation at odds over the false distinction between freedom and security. Crisis on Infinite Earths was a necessary bit housecleaning, with some strong storytelling. They're worthwhile and fun. But enough grandeur already. Just tell me a decent story and I'm there.

My point is that comics deserve to be taken seriously, AS COMICS. Museums are great and comics deserve a place in them. But please don't damn them with faint praise by insisting on the "graphic novel" badge to "legitimize" the work. A great show of Comic Book Art needs no excuses for itself.

It's a bloody comic book. That's all it needs to be. If it's a good one, let it stand on its own merits.

Monday, May 17, 2010

Original Art Sundays # 41a: Uptown Girl

Grades are done, and technically it's not Sunday any more, but here we go anyway.

No scanner access until later this week, so I am posting an image I did for a friend ages ago. Seeing him with his wife and daughter at Minneapolis Spring Con reminded me of this piece I did for Bob Lipski's Uptown Girl web page.

If you've not read Uptown Girl, it's fun and thought-provoking, simple and clean without being dumbed down.

Bob is hard at work on an Uptown Girl graphic novel. I am eager for the final product!

New page again later this week!

No scanner access until later this week, so I am posting an image I did for a friend ages ago. Seeing him with his wife and daughter at Minneapolis Spring Con reminded me of this piece I did for Bob Lipski's Uptown Girl web page.

If you've not read Uptown Girl, it's fun and thought-provoking, simple and clean without being dumbed down.

Bob is hard at work on an Uptown Girl graphic novel. I am eager for the final product!

New page again later this week!

Thursday, January 7, 2010

Top 10 Comics of 2009: # 4: Whatever Happened to the World of Tomorrow?

The world of comics can be rather pessimistic at times. Worlds destroyed, brutality and amorality (especially in the recent Punisher books, which turn vengeance into self-parody), and, as Scott McCloud observes in ZOT!, justice should be more than a punch in the mouth.

Thank the Diety for the personal memoir.

A few years ago, Brian Feis, whose line style is quite similar to Tom Batuik's work on Funky Winkerbean, gave us the quiet revelations of the award- winning Mom's Cancer.

Now he's back, with this summer's Whatever Happened to the World of Tomorrow? Hereafter I wil use the acronym WHTTWOT to save my fingers.

Thank the Diety for the personal memoir.

A few years ago, Brian Feis, whose line style is quite similar to Tom Batuik's work on Funky Winkerbean, gave us the quiet revelations of the award- winning Mom's Cancer.

Now he's back, with this summer's Whatever Happened to the World of Tomorrow? Hereafter I wil use the acronym WHTTWOT to save my fingers.

It should be noted that the front bottom scenery is a die-cut cardstock sort of half a dustjacket. The effect, reminiscent of Chris Ware's Acme Library in design, is subtle and eloquent.

The book, a proper graphic novel rather than a collection of floppies, as are so many mislabeled GNs, begins with a lad and his dad attending the 1939 New York World's Fair.

While at the fair, both are astounded by the promise of the future it offers.

The boy embraces the streamlined possibilities of the future promised in 1939.

He's given a comic book while attending. Using a surprisingly effective metafiction (I loathe the overuse of that term but it applies here), the comic reappears at various points in WHTTWOT. Its evolution echoes not only that of comics themselves but that of the society in which they, and the boy, grow. The comics contained in the larger narrative are printed on a yellowed newsprint stock simulating period books, a nice touch!

The boy and the man remain fascinated with technology, especially as it relates to flight and the space program, even when it fails to live up to its anticipated promise, and offers new possibilities instead. As the world grows around them, we see the father and son respond to that growth and perceive their own place in the world shifting.

As the two age, they do not lose their hope, despite the technological utopia's measured successes.

When the subsequent generation- the daughter of the son who saw the proposed wonders in 1939- is seen living on the moon, her father and grandfather are there to share in the fulfillment of their dreams and to nurture the birth of hers.

It's a little gosh-wow in spots, and the inevitable teenage clash between father and son over rock music plays out very softly, as some light-hearted jibes rather than full-blown rebellion. But the key to the book is the idea that even if things don't turn out as planned, optimism is always a possibility, even a desirable goal. Beyond that, the father and son trust one another to face whatever comes together.

The story has its holes. Our heroes revel in the docking of the Apollo and Soyuz missions, but no mention is given to the Challenger disaster.

It should be noted that the creator, Brian Fies, will be Artist-in-residence at the Charles Schulz Museum on Saturday, Jan. 9.

If there's a TPB of this by the time it's needed, I hope to use WHTTWOT? as a text the next time I teach Graphic Novel.

Tomorrow: if I can hunt up the right dream, #3 on the best comics of 2009.

Sunday, January 3, 2010

Original Art Sundays, No. 23: A Private Myth, p. 1

Every now and then, I attempt a Magnum Opus, usually in comics form. My last one was a graphic novel about transsexual life (whatever that is) called Transcending. I got the whole thing plotted and got about 20 pages into it when I ran out of steam. Some of those pages have been posted in other locations a couple years ago (by me).

My most recent attempt was a screenplay that I wrote a couple years ago titled Private Myths. I let a few people read it, but not much happened with it. As is my way, I was not particularly agressive in pursuing its marketing.

I toyed with making it into a novel, pursuing a production company (I'm not all that connected but I do know a couple people), and getting a decent video camera and trying to film it myself.

I tweaked the title to A Private Myth. Then I threw the first page up on the board.

I completed page 1 in just a few days, and it stayed there for several months. Yesterday I moved on to the next page, and hope to use this forum as an excuse to prod myself to finish it, slowly, slowly, a page a week.

This first page is from a digital photo, not a scan. It needs a few tweaks and tweakettes, which will be made in a couple weeks.

The storyline will not be apparent for the first few pages. But have faith. There's love, passion, magical realism, maybe mental illness, farming, dogs and cats, and lesbians.

What more could you ask?

The title comes from Joseph Campbell:

Dreams are private myths, myths are public dreams....

My most recent attempt was a screenplay that I wrote a couple years ago titled Private Myths. I let a few people read it, but not much happened with it. As is my way, I was not particularly agressive in pursuing its marketing.

I toyed with making it into a novel, pursuing a production company (I'm not all that connected but I do know a couple people), and getting a decent video camera and trying to film it myself.

I tweaked the title to A Private Myth. Then I threw the first page up on the board.

I completed page 1 in just a few days, and it stayed there for several months. Yesterday I moved on to the next page, and hope to use this forum as an excuse to prod myself to finish it, slowly, slowly, a page a week.

This first page is from a digital photo, not a scan. It needs a few tweaks and tweakettes, which will be made in a couple weeks.

The storyline will not be apparent for the first few pages. But have faith. There's love, passion, magical realism, maybe mental illness, farming, dogs and cats, and lesbians.

What more could you ask?

The title comes from Joseph Campbell:

Sunday, May 10, 2009

An excuse to post something wonderful!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)