Anyone versed in science fiction, fantasy and horror knows his work. Many of us (like me) begin with it.

I found a copy of R is for Rocket in my grade school library. Coupled with the short story The Man in a Boy's Life SF anthology I got somewhere, I developed a fascination with his sensitivity and use of language, even if I didn't fully understand it at age 8.

But as I did with Lord of the Rings and The Stars My Destination, I kept coming back to the work(s), finding new treats and possibilities every time.

My favorite works of his remain unchanged over the last ten years or so: his screenplay for John Huston's Moby Dick, the novel Something Wicked This Way Comes, The Martian Chronicles, and some of his SF poetry.

THEY HAVE NOT SEEN THE STARS

They have not seen the stars,Not one, not one

Of all the creatures on this world

In all the ages since the sands

First touched the wind,

Not one, not one,

No beast of all the beasts has stood

On meadowland or plain or hill

And known the thrill of looking at those fires.

Our soul admires what they,

Oh, they, have never known.

Five billion years have flown

In turnings of the spheres,

But not once in all those years

Has lion, dog, or bird that sweeps the air

Looked there, oh, look. Looked there.

Ah, God, the stars. Oh, look, there!

It is as if all time had never been,

Nor Universe or Sun or Moon

Or simple morning light.

Those beasts, their tragedy was mute and blind,

And so remains. Our sight?

Yes, ours? to know now what we are.

But think of it, then choose. Now, which?

Born to raw Earth, inhabiting a scene,

And all of it no sooner viewed, erased,

As if these miracles had never been?

Vast circlings of sounding fire and frost,

And all when focused, what? as quickly lost?

Or us, in fragile flesh, with God's new eyes

That lift and comprehend and search the skies?

We watch the seasons drifting in the lunar tide

And know the years, remembering what's died.

But what I'd really like to talk about is his work in comics.

This is not intended to be exhaustive. It's a retrospective of my experience of the man's work.

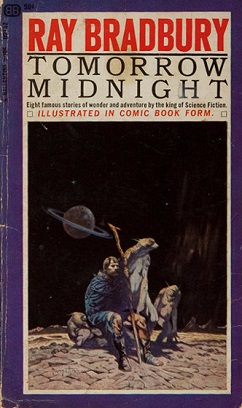

The story of his bemused chiding of EC publisher Max Gaines and editor Al Feldstein is pretty common knowledge. My first exposure to these stories, given the lack of reprints in the late 1960s and early 1970s, was in the form of a couple Ballantine paperback collections of the EC stories, Tomorrow Midnight and The Autumn People. Both had Frazetta covers.

In 1978, when Russ Cochran's EC Reprint series of slip-cased hardcover editions began to come out, I had a subscription. In devouring the supporting material, I learned of the infamous letter to EC, politely chiding them for neglecting to pay his royalties on a story of his that they'd actually lifted!

The upshot, of course, was that he agreed to further adaptations. One of these, The Flying Man, contains eloquent art by one of my personal favorites, Bernard Krigstein.

I'm sure I read other Bradbury adaptations in comics over the years, but the next one that triggers in my memory is a poem on Viking Lander I that was included in Mike Frederich's "ground level" comic experiment, Star Reach, issue 6. The idea behind the "ground level" movement was that comics could take the energy and freedom of the undergrounds and temper it with more, ahem, lucid storytelling of overground, or mainstream comics. Sometimes it worked, sometimes not. The issue containing the Bradbury poem was particularly strong overall, incorporating a delightfully aggressive and melancholy Elric story by old Madison acquaintance Steven Grant and illustrator Bob Gould. The Bradbury poem in that issue was framed by an Alex Nino illustration, enhancing my burgeoning fascination with Fillipino comic artists.

I'm sure I read other Bradbury adaptations in comics over the years, but the next one that triggers in my memory is a poem on Viking Lander I that was included in Mike Frederich's "ground level" comic experiment, Star Reach, issue 6. The idea behind the "ground level" movement was that comics could take the energy and freedom of the undergrounds and temper it with more, ahem, lucid storytelling of overground, or mainstream comics. Sometimes it worked, sometimes not. The issue containing the Bradbury poem was particularly strong overall, incorporating a delightfully aggressive and melancholy Elric story by old Madison acquaintance Steven Grant and illustrator Bob Gould. The Bradbury poem in that issue was framed by an Alex Nino illustration, enhancing my burgeoning fascination with Fillipino comic artists.Bradbury slipped in and out of my radar over the ensuing years. I was fascinated by the film adaptation of Something Wicked This Way Comes, despite the depiction of rolling hills in Illinois!

The next comic book work involving Bradbury that I remember reading was the 1985 adaptation of Frost and Fire, part of a series of ambitious graphic novel SF adaptations of classic SF(and some noteworthy newer works, like Arthur Byron Cover's Space Clusters, again illustrated by Alex Nino!). Frost and Fire was illustrated by veteran inker Klaus Janson, most celebrated at the time for his work with Frank Miller on Miller's initial Daredevil run. It's a successful collaboration, seamless in most places. The Bill Sienkiewicz cover art is well suited to the tone of the story.

Following that, there were the Topps adaptations of Bradbury's work. Topps was a short-lived but ambitious 1990s comic book publisher, an extension of the Topps bubblegum card company. As you might expect from that, most of their line consisted of licensed properties, including The Lone Ranger, The X-Files and Xena. I recall two series, Ray Bradbury Comics (collected as multiple volumes of The Ray Bradbury Chronicles), a serialized version of The Martian Chronicles, and a one-shot of The Illustrated Man. As an anthology, the latter was uneven but usually worthwhile. I recall a particularly sensitive collaboration with P. Craig Russell on the story The Visitor. I've gushed over Russell's work in the past. Suffice to say that despite some printing issues, the work is worth searching out.

Following that, there were the Topps adaptations of Bradbury's work. Topps was a short-lived but ambitious 1990s comic book publisher, an extension of the Topps bubblegum card company. As you might expect from that, most of their line consisted of licensed properties, including The Lone Ranger, The X-Files and Xena. I recall two series, Ray Bradbury Comics (collected as multiple volumes of The Ray Bradbury Chronicles), a serialized version of The Martian Chronicles, and a one-shot of The Illustrated Man. As an anthology, the latter was uneven but usually worthwhile. I recall a particularly sensitive collaboration with P. Craig Russell on the story The Visitor. I've gushed over Russell's work in the past. Suffice to say that despite some printing issues, the work is worth searching out.Those are my memories of Ray Bradbury's work in comics. I know it's far from a comprehensive list of comic book work , if such a thing exists.

And it's not intended to be complete.There must be a Bradbury comic book bibliography, but I've not found one. I note with some sadness that there's no Bradbury entry at Lambiek, a site I've come to regard as a source of record on comic matters.

I did have one last comic book related Bradbury encounter. My colleague Dana Andrews and I were haunting the dealer's floor, down by Artist's Alley at SDCC a few years ago. We heard a loud shout behind us- "Make way, make way! Make way for Ray Bradbury!" His honor guard forming a snowplow wedge, Ray Bradbury was wheeled by us, generating spontaneous applause as he passed. I gave him a smile, which I remember him returning. No way of knowing if that smile came from his head or my wishful thinking, but he did have a reputation as having a bit of an eye for the ladies.

Sad to think there will never be another Ray Bradbury story, barring printings of works already scheduled, if such there be. But like his peers, the other humanists of SF (Sturgeon, Simak, and Kress come to mind in this context), I think the line the fictional version of Twain uttered in an episode of ST: TNG comes to mind: "All I am is in my books."

His eloquence shows in this classic scene. Goodbye, Grand Master of Science Fiction.

And then the son saves him, and then he saves his son, and they live to the happy ending.